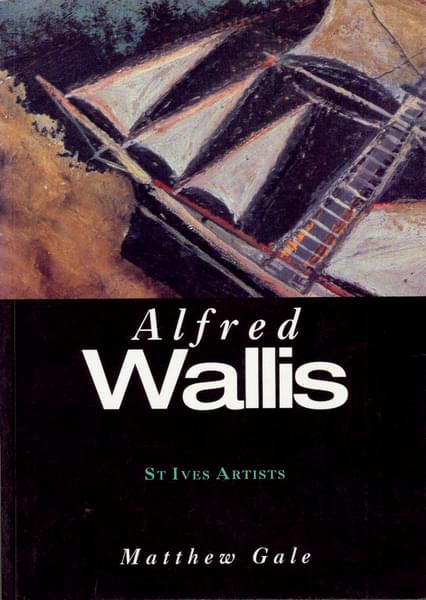

Alfred Wallis

Alfred Wallis became famous only in old age after Ben Nicholson paid his first visit to St Ives in Cornwall with his friend Christopher Wood. Wandering through the narrow streets near Porthmeor Beach in 1928, the pair suddenly discovered – through an open door in Back Road West – some astonishingly original drawings of ships. Excited, they entered the cottage and found the 73-year-old Wallis working at a table. When Nicholson and Wood asked him if they could buy some pictures, Wallis confessed that he had never thought of selling them – he only painted “for company” to combat loneliness following his wife’s death. But after he told the young artists that they could “give me what you like” for the work, they made sure that Wallis soon became admired as a genuine “primitive” in avant-garde circles.

Wallis, a fisherman, had not entertained becoming an artist before the age of 70, and tragedy often afflicted his long, audacious and defiantly unpredictable life. In 1876, at the age of 21, he crossed the Atlantic on a brigantine aptly named Belle Adventure. He married Susan Ward the same year, but both their children died soon after birth. Wallis sailed around Scotland on marathon fishing expeditions before settling in St Ives to establish his Marine Stores. Then, following his wife’s death and the closure of the Stores, he stayed mainly indoors and focused obsessively on painting. But in 1937 he was knocked down by a car, and remained severely shaken by the accident. By 1941 he had begun to suffer from persecution mania, and his health declined so rapidly that he died in a workhouse in Madron, Penzance a year later.

Today, Wallis is justly prized for his vigorous, highly simplified and robustly original vision, and Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge have mounted illuminating surveys of his work. Jim Ede, who formed the collection in Kettle’s Yard, became a patron of Wallis during the 1930s and acquired many of his finest works. Some of the letters Wallis wrote to Ede are included in this show, and their quirky grammar is a delight to read. In one note, sent with a bundle of paintings tied together with string in 1938, Wallis declares: “I think their They are so good if not Better i have don.”

Although he knew nothing about the professional art world, Wallis was stimulated by the support given to him – not only by Nicholson and Ede but also by the influential critic Herbert Read, who in 1933 illustrated Wallis’s work in an immensely influential book called Art Now. Wood gave Wallis a sizeable canvas in about 1928, and it encouraged the Cornishman to paint a powerful image called “Seascape – Ships Sailing Past the Longships”. A dark and ominous work, it shows a large vessel belching black smoke from a funnel as it moves towards a very phallic lighthouse thrusting into the oppressive sky. The three small ships at the base of the painting look very vulnerable; Wallis must have known all about the frailty of craft from his own life at sea.

Most of Wallis’s paintings were executed on scraps of old cardboard boxes, and he would cut them into irregular shapes that intensify the sense of fragility. Some focus on moments of extreme peril: “Small Boat in a Rough Sea” reveals the moment when a sailing vessel is about to keel over and become overwhelmed by remorselessly towering waves. This sense of danger might explain why the harbour plays such a crucial role in many of Wallis’s paintings: it is seen, time and again, as a consoling haven where all the manifold anxieties of maritime life can at last be set aside.

As his work developed, Wallis constantly disclosed new sources of unease. In a strange painting called “Boats before a Great Bridge”, he emphasises the monumental solidity of the looming structure compared with the puny vessels passing its awesome arches. Wallis sought comfort in religion, reading the Bible every day. Although people tend to play a minor part in his work, he did paint a haunting picture called “Crucifixion or Allegory with Three Figures and Two Dogs”. The agony of the child-like, crucified figures, one standing on top of the other, seems to frighten the animals, while a solitary man in profile passes below as if unable to see their suffering.

Most of the time Wallis preferred to concentrate on his beloved boats and ships. He even believed that these vessels had “a soul, a beautiful soul shaped like a fish”. Perhaps that is why, in a bizarre painting called “Land, Fish and Motor Vessel”, two gigantic fish are the same size as the twin-funnelled craft sailing nearby. But then in 1942, just before he died, Wallis painted “Death Ship”, an uncompromisingly funereal image in which the gloomy vessel seems bent on carrying away the artist himself to extinction.