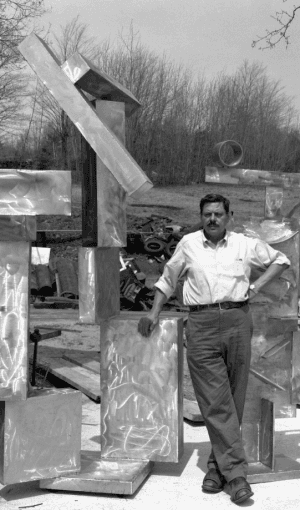

David Smith

David Smith was best known as one of the most important and influential American sculptors of the mid-20th Century. He took ideas from Cubism, Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism and transformed them into something entirely idiosyncratic.

Smith studied in New York, having been encouraged to enrol at the Art Students League by his first wife, fellow sculptor Dorothy Dehner. Initially, Smith focused on two-dimensional media, although he began to experiment with relief formats. However, in the early 1930s, he was exposed to the welded sculptures of Pablo Picasso and Julio González in reproductions shown to him by fellow artist John Graham, a vital figure in bringing European avant garde currents to the USA. Smith was impressed by the idea that welding, which he had learned while working in industry, could be turned to artistic purposes.

Smith was soon creating evocative, experimental works which often featured three-dimensional collages of various objects, mixing his media and producing results which fused the figurative and the abstract. Smith’s growing success and recognition during the post-war years meant that he increasingly had access to an abundance of resources and materials, working on an ever larger scale. From 1950 onwards, when he was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship, he was able to create large-scale, totemic sculptures, essentially working in two styles: some show a deft sense of almost calligraphic line while others involve the use of broad, often geometric, masses of metal.

His best works are seen as sculptural counterparts to the works of the Abstract Expressionists. Many of these, he counted among his friends and colleagues. Before the advent of Abstract Expressionism, he had been involved in the legendary Works Progress Administration, which featured within its ranks artists such as Arshile Gorky, Philip Guston, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Ad Reinhardt and Mark Rothko. It was against this backdrop that Smith forged his new path in sculpture. This is reflected in the fact that his sculptures were sometimes intended to be viewed from a single place, as though they were pictures in three dimensions. As Smith himself explained, ‘I belong with painters.’

Featured Artists

- Albers Anni

- Ancart Harold

- Andre Carl

- Avery Milton

- Baldessari John

- Barnes Ernie

- Castellani Enrico

- Clough Prunella

- Crawford Brett

- Dadamaino

- de Tollenaere Saskia

- Dyson Julian

- Elsner Slawomir

- Freud Lucian

- Gadsby Eric

- Gander Ryan

- Guston Philip

- Hartung Hans

- Hayes David

- Held Al

- Hepworth Barbara

- Hill Anthony

- Hitchens Ivon

- Hockney David

- Hutchinson Norman Douglas

- Jenney Neil

- Katz Alex

- Kentridge William

- Knifer Julije

- Kusama Yayoi

- Le Parc Julio

- Leciejewski Edgar

- Léger Fernand

- Levine Chris

- Marchéllo

- Martin Kenneth

- Mavignier Almir da Silva

- Miller Harland

- Mitchell Joan

- Modé João

- Moore Henry

- Morellet François

- Nadelman Elie

- Nara Yoshitomo

- Nesbitt Lowell Blair

- Nicholson Ben

- O'Donoghue Hughie

- Pasmore Victor

- Perry Grayson

- Picasso Pablo

- Pickstone Sarah

- Prehistoric Objects

- Riley Bridget

- Ruscha Ed

- Sedgley Peter

- Serra Richard

- Shrigley David

- Smith Anj

- Smith Richard

- Soto Jesús Rafael

- Soulages Pierre

- Spencer Stanley

- Taller Popular de Serigrafía

- The Connor Brothers

- Vasarely Victor

- Vaughan Keith

- Whiteread Rachel

- Wood Jonas