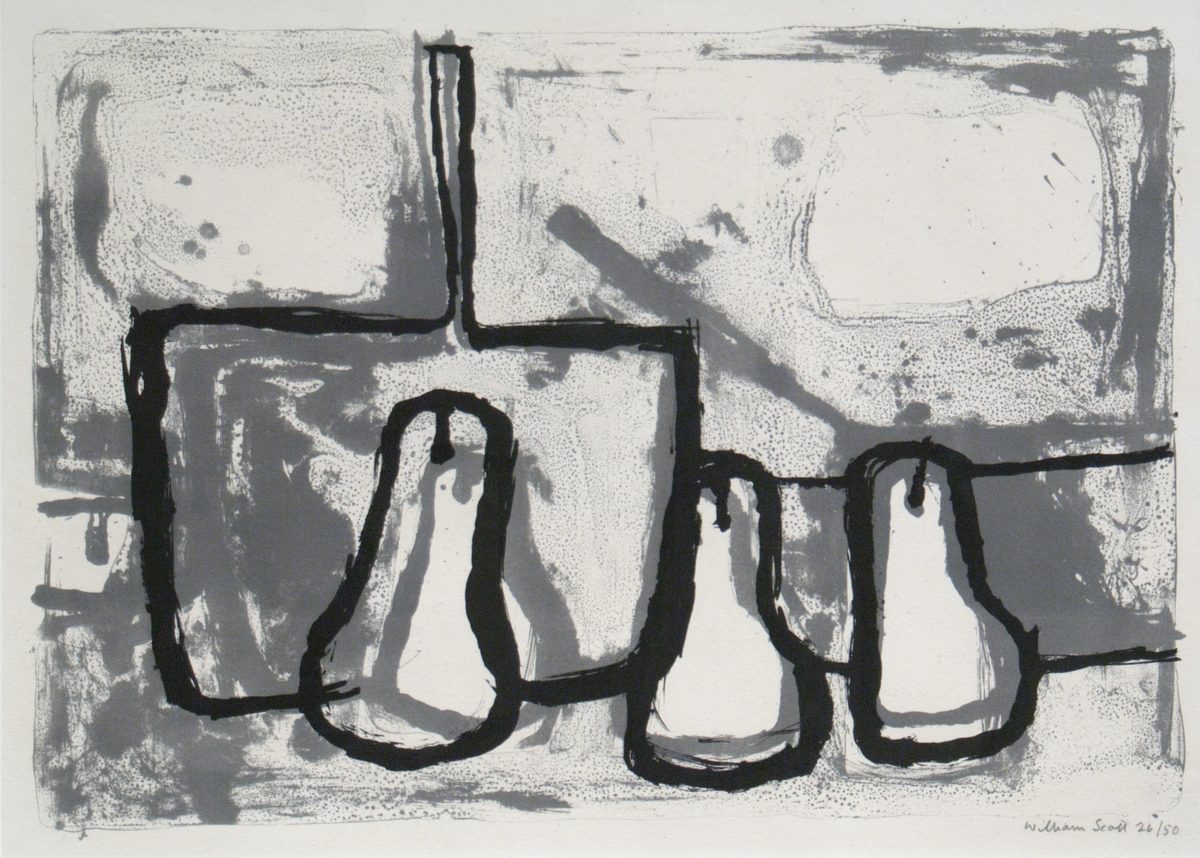

Still Life – Three Pears and Pan

The still lives which Scott chose to depict, and which are instantly recognisable, were arrangements of pots and pans, eggs, pears, bottles and fish on a tabletop. Although his initial inspirations for this genre may have included admiration for the work of French painters such as Chardin and Braque, his criteria for judging whether his own still life paintings were a success were wholly different from those of the great artists before him. Unlike anyone else, Scott chose kitchen utensils as a recurring theme in his work because, he explained, he found them “completely uninteresting”* as objects. Such simple everyday items were merely building blocks for his paintings: they came without associations for him and, he hoped, the viewer. He felt that, with this subject matter, he was free to explore the arrangements and relationships between these ordinary shapes and hopefully to create tension from nothing. Unconsciously, his choice of such mundane objects mirrored the more general social austerity of ration-era post-war Britain and Scott, like all painters must, projected something in his still lives of the rationed age in which he lived. Nonetheless, he was incredibly inventive. Prolonged experimentation with the grouping of these objects in the final years of the 1940s, and again in the mid-1950s after a brief flirtation with abstraction, resulted in a mysterious dynamic – the individual objects in the pictures developed sexual characteristics. In seemingly innocent still lives, scenes of erotic drama could be deciphered by those familiar with Scott’s work. Scott himself often declined to comment upon this interpretation**, but his intentions were direct and unmistakable. Not only had his inanimate, everyday objects become animated, they had acquired personalities and, more importantly, gender.

Still Life – Three Pears and Pan of 1955 , an important early privately printed lithograph, relates directly to a series of paintings of the same year. In their common subject matter of pans and pears, both the paintings and this print display the sexual animations which were “the secret in the picture”***, albeit more subtly than his works circa 1950. Again, in Scott’s career as a printmaker, we see a highly resolved group of painted work almost summarised by the production of a print. The heavily worked surfaces of this group of paintings have echoes in the chaotic, vibrating, layered construction of the print. The overlapping shapes are reinforced and bound together, as all these scenes are, by strong black lines. Scott’s style at this time is relatively figurative - the objects which become simple shapes and forms in the artist’s later work are still easily identifiable. The emphasis of the print is undiluted by abstraction, and seems only to be concerned with the communication of some veiled narrative. The grouping of the still life subject is designed to emphasise the suggestive closeness of the component objects, however their literal interpretation is confused by Scott’s deliberately ambiguous personification. One can never be certain as to the exact reading of the scene in Still Life – Three Pears and Pan, in fact it is highly doubtful that there is only one intended meaning. Consider in this print, for example, how the aroused male/pear presses against and into the inviting female pan/body on the left of the composition, and how the object genders thus-assigned are then contradicted by the male pan on the right. The phallic profile of the panhandle rubs against the female pan and poises threateningly between pears which now suggest the parted legs of another woman. Ambiguous indeed, and it is tempting, when looking at these scenes of Scott’s, to wonder whether he occasionally obfuscated through modesty, nervous perhaps that he might be seen to be going too far. But then again, look afresh at the composition and perhaps the whole is to be seen as a waiting female figure, her lover approaching with a tender outstretched arm? Visual duality was highly important to Scott.

Also known as Three Pears, impressions of this print were first exhibited at the 1956 Cincinnati Biennial and also at the Redfern Gallery, London later that year.

*Alan Bowness, William Scott: Paintings, London, Lund Humphries 1964, p.10

**Ibid., p.8, Bowness quotes Scott as saying “These objects now take on another meaning, which is obscure, and I don’t personally like to point it out”

***Ibid., p.8. Scott refers specifically to Still Life of 1951, however Bowness immediately relates this comment to a series of paintings and describes the “erotic, sensual element” in general as “so important”.

Still Life – Three Pears and Pan

- Artist

- William Scott (1913-1989)

- Title

- Still Life - Three Pears and Pan

- (also known as)

- Three Pears, or Three Pears and a Pan

- Medium

- Lithograph

- Date

- 1955

- Sheet

- 40.4 x 60.6 cm: 17 3/8 x 26 in.

- Image

- 35.5 x 50.8 cm: 14 x 22 7/8 in.

- Edition

- From the edition of 50, although it is highly doubtful that more than 15 were printed, signed and numbered by the artist

- Printer

- Printed at the Bath Academy of Art, Corsham Court

- Publisher

- Published privately

- Literature

- Archeus 10

- Reference

- C16-28

- Status

- No Longer Available

Available Artists

- Albers Anni

- Ancart Harold

- Andre Carl

- Avery Milton

- Baldessari John

- Barnes Ernie

- Castellani Enrico

- Clough Prunella

- Crawford Brett

- Dadamaino

- de Tollenaere Saskia

- Dyson Julian

- Elsner Slawomir

- Freud Lucian

- Gadsby Eric

- Gander Ryan

- Guston Philip

- Hartung Hans

- Hayes David

- Held Al

- Hepworth Barbara

- Hill Anthony

- Hitchens Ivon

- Hockney David

- Hutchinson Norman Douglas

- Jenney Neil

- Katz Alex

- Kentridge William

- Knifer Julije

- Kusama Yayoi

- Le Parc Julio

- Leciejewski Edgar

- Léger Fernand

- Levine Chris

- Marchéllo

- Martin Kenneth

- Mavignier Almir da Silva

- Miller Harland

- Mitchell Joan

- Modé João

- Moore Henry

- Morellet François

- Nadelman Elie

- Nara Yoshitomo

- Nesbitt Lowell Blair

- Nicholson Ben

- O'Donoghue Hughie

- Pasmore Victor

- Perry Grayson

- Picasso Pablo

- Pickstone Sarah

- Prehistoric Objects

- Riley Bridget

- Ruscha Ed

- Sedgley Peter

- Serra Richard

- Shrigley David

- Smith Anj

- Smith Richard

- Soto Jesús Rafael

- Soulages Pierre

- Spencer Stanley

- Taller Popular de Serigrafía

- The Connor Brothers

- Vasarely Victor

- Vaughan Keith

- Whiteread Rachel

- Wood Jonas