Untitled [Water]

David Hockney and Water

“Water, the idea of drawing water, is always appealing to me. If it’s clear water anyway, transparent water. You can look on it, through it, into it, see it as volume, see it as surface…the idea of representing it has always rather fascinated me and I keep going back to it."

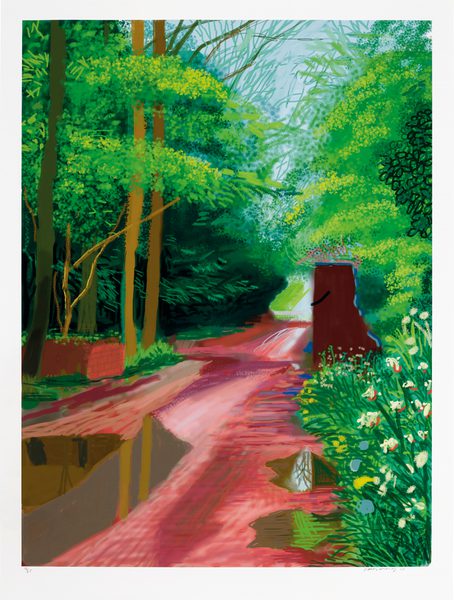

One aspect of the origins of David Hockney’s relationship between himself as a painter and the subject of water has been particularly well documented and often retold: the moment of his arrival by air to Los Angeles in 1963, looking down from the airplane window to see thousands of rectangles of blue swimming pools. “..As I flew over San Bernardino and saw the swimming pools and the houses and everything and the sun, I was more thrilled than I have ever been in arriving in any city.”

Hockney didn’t wait for success to find him. Earlier in 1963 the dealer John Kasmin had given the 26 year-old artist his first solo exhibition in London – it was completely sold out. Hockney used part of his earnings from that show to visit America and in particular Los Angeles, the city to which he had long waited to travel. He had recreated scenes from LA-published magazines, such as the cult Physique Pictorial, as part of his work at the Royal College of Art, as well as for the Kasmin exhibition. Domestic Scene, Los Angeles for instance, which depicts a man standing in a shower’s cascade of water whilst having his back washed, was painted before he had visited the city, and was based on such an image. Hockney would move there to live full-time shortly afterwards.

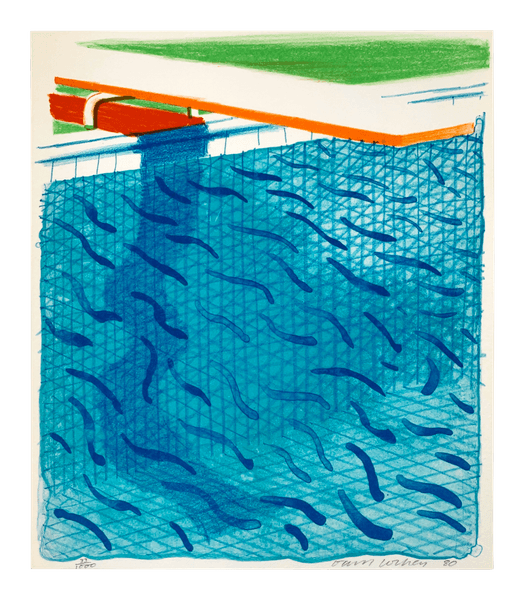

Of course it is Hockney’s swimming pool paintings for which he was first acclaimed in America, and for which he is chiefly still celebrated. However, when the significance of the pool equals California equals sexual freedom is noted and moved past, in the depiction of water, one of his earliest and few journeys into any form of abstraction becomes more apparent. Hockney would always resist any observation that he entertained the abstract at that early stage, but nevertheless explained, “In the swimming pool pictures, I had become interested in the more general problem of painting the water, finding a way to do it. It is an interesting formal problem; it is a formal problem to represent water, to describe water, because it can be anything. It can be any colour and it has no set visual description.” The sheer number of abstract arrangements Hockney found to portray just the surface of water alone at that time is truly astonishing. Lines run across his pools in squiggles, camouflage patterns are used, and variegated patches of colour are all employed in seemingly infinite combinations. Whether he liked it or not, the earliest and most powerful tool available to Hockney to explore the subject of water was a methodology that was abstraction in all but name to him. He eschewed the movement vocally whilst at the Royal College, later stating “To me painting is picture making. I am not that interested in painting that doesn’t depict the visible world. I mean, it might be perfectly good art it just doesn’t interest me that much.” In 1965 Hockney produced a set of prints called A Hollywood Collection, in which one of the subjects is titled Picture of a Pointless Abstraction Framed under Glass: this sums up the artist’s discomfort with the whole notion rather well. The derisive manner in which the artist had largely avoided abstraction was already well known, yet here it was in his paintings, even if the sum total of all those abstract details was a struggle for realism.

When painting one of his most famous works from the period, A Bigger Splash in 1967, he was presented with possibly his most obvious opportunity to embrace abstraction, at least in part. Whereas many painters might channel Jackson Pollock and flick liquid paint at the canvas, or use chaotic, expressive mark-making to represent the splash, Hockney did precisely the opposite. He painstakingly reproduced the splash from a photograph using tiny brushes, layering the shapes made by the upsurging arcs of water, glazing small details of transparency and faithfully recreating the drops. It took him two weeks to get the splash looking just as he wanted it to. “When you photograph a splash, you’re freezing a moment and it becomes something else. I realise that a splash could never be seen this way in real life, it happens too quickly. And I was amused by this, so I painted it in a very, very slow way.” The work defined Hockney’s painting at that time, becoming the most well-known snapshot linking him and his new LA life.

The depiction of flowing water provided further technical challenges which Hockney overcame in novel ways. Apart from the shower scenes, early works by the artist show water in motion in various settings. Uniform sprays from sprinkler heads water perfect LA lawns ; rain makes its way into a number of compositions, spattering and pooling as it touches down. In a painting and accompanying print, he presented Different Kinds of Water Pouring into a Swimming Pool, Santa Monica. Such a subject afforded Hockney the equivalent of a visual exercise book where he played with different arrangements of curves and grades of translucency, all while refining his unique style. The dynamic form of water could be interpreted a thousand different ways he seemed to be showing us but, there was never to be any doubt that, no matter how abstract or how far he varied from water’s base palette of blue, green and white, Hockney’s hand is unmistakeable. For a man who once said “Water, I can’t describe it with words, it’s so elusive”, he certainly had no shortage of vocabulary when it came to the brush.

Hockney quickly and astutely realised that he risked his growing reputation by repeating himself too often, so made a conscious decision to leave the swimming pool motif for much of the early 1970s, with the exception of his 1972 masterpiece Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures). It wasn’t until 1978 that, quite by chance due to a lost driving licence, he would give the swimming pool one of his most concentrated periods of attention. Unable to take a planned transcontinental drive he went to upstate New York to visit his friend, the printer Ken Tyler, who had a house and a workshop there. Tyler had been excited to show him a new technique involving liquid paper which he had invented for Ellsworth Kelly. The process involved making gallons of fresh paper pulp, which could be used like paint and hand-coloured whilst wet before being pressed flat. It wasn't printmaking, it was painting with the paper itself, a process that the artist had to perform himself by hand. Each variant of each image would be an unique painted work and Hockney was sufficiently intrigued to stay, and so the great Paper Pools series came about.

Hockney studied Tyler's pool in New York at different times of day and night through Polaroid shots and subsequent drawings in order to muse upon the many different light and colour changes that the pool underwent. From these drawings, Hockney created cloisonné-like moulds, pouring liquid coloured pulp directly over flat sheets of wet, newly made paper. The artist then put the finishing touches on the work by directly applying coloured pulp and liquid dyes freehand. In this new medium, Hockney utilised copious amounts of water in his paradoxical quest to capture in a still image the constant rippling on the pool's surface. As the artist noted in his essay on the series, “I kept looking at the swimming pool; and it's a wonderful subject, water, the light on the water. And this process with paper pulp demanded a lot of water; you have to wear boots and rubber aprons. I thought, really [what] I should do [is], find a watery subject for this process, and here it is..”

Hockney produced more than two dozen variants of the Paper Pools, and the drawings he made became the basis for a further eleven Lithographs of Water Made of Lines. The book Paper Pools, published in 1980 and which described the entire period, was issued with a small lithograph of a diving board, pool and shadow in a signed edition of 1000. The act of signing 1000 prints alone was enough to leave Hockney in no doubt that, for the moment, he “had done enough pools”.

Considering Hockney’s proximity to the ocean itself, as a subject it did not enter his work in a meaningful way until he bought a beach house in Malibu in 1988. For a period the waves of the Pacific served as a backdrop to many images made from, and of, the house and its interior. Despite the ever-present vastness of the sea outside his window, nothing would hold the artist’s attention as firmly as the ever-changing kaleidoscopic swimming pool water being struck by California sunlight. Hockney finally embraced the indelibility of his association with the subject that year, taking a ladder and rollers down inside an empty swimming pool to paint the lining of the Roosevelt Hotel pool in Hollywood. The huge mural he created on the floor and walls of the Roosevelt pool comprises a freehand design of blue curved lines, which forms a complete, interwoven pattern when the water is still but dances and shimmers when it is disturbed. The fact that Californians could now swim in a Hockney pleased the artist no end, so much so that his own pool at his home in the hills is decorated the same way. An overhead polaroid composite of a swimmer in this pool was used as one of the fifteen official Olympic posters for the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

Hockney’s swimming pool paintings exerted a powerful influence on other artists. The 2012 exhibition ‘Backyard Oasis: The Swimming Pool in Southern California Photography, 1945–1982’, held at the Palm Springs Art Museum, showed the enabling example that Hockney’s paintings presented for several generations of photographers. The swimming pool was already a central concern of celebrity photography and ‘beefcake’ images, but Hockney’s exploration of it in the major paintings of the 1960s and early 1970s encouraged more adventurous artistic exploration of the theme. Nine Swimming Pools (1968) by Ed Ruscha, a friend of Hockney’s since his arrival in LA, is a good example: an assemblage of photographs of uncannily deserted and peaceful backyard pools, all shot from low angles, which come to seem like formalistic variations on Hockney’s theme. It is also arguable that the work of painters such as Eric Fischl would not have developed in the same way, or at all in similarity, without Hockney’s images already being in existence. As recently as 2017, the Scottish painter who has risen to some significance, Caroline Walker, created a series of paintings in Palm Springs which fuse a Hopperesque viewpoint with a homage to the pools of Southern California.

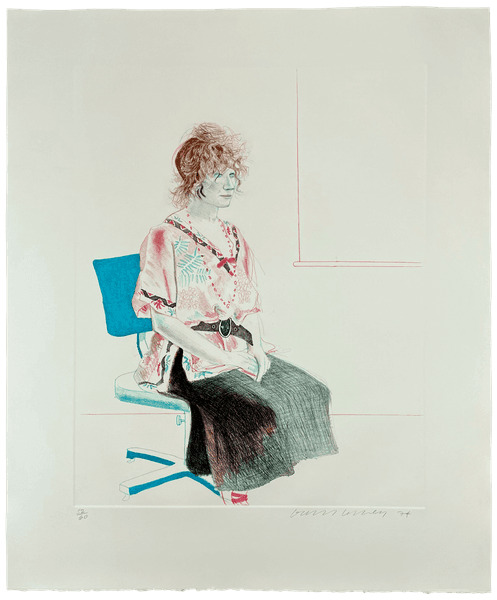

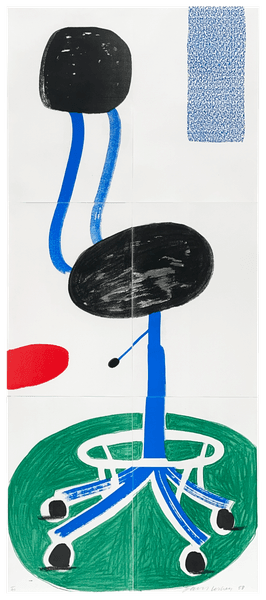

Untitled [Water]

- Artist

- David Hockney (b.1937)

- Title

- Untitled [Water]

- Medium

- Coloured pencil on paper

- Date

- 1966

- Size

- 13 ¾ x 10 in : 35.0 x 25.1 cm

- Framed size

- 16 ¼ x 12 ¾ in : 41.5 x 32.5 cm

- Inscriptions

- Signed with the artist's initials and dated 'DH. '66' lower right

- Provenance

- Kasmin Gallery, London

Private Collection - Reference

- AC25-02

- Status

- Available

Available Artists

- Albers Anni

- Ancart Harold

- Andre Carl

- Avery Milton

- Baldessari John

- Barnes Ernie

- Castellani Enrico

- Clough Prunella

- Crawford Brett

- Dadamaino

- de Tollenaere Saskia

- Dyson Julian

- Elsner Slawomir

- Freud Lucian

- Gadsby Eric

- Gander Ryan

- Guston Philip

- Hartung Hans

- Hayes David

- Held Al

- Hepworth Barbara

- Hill Anthony

- Hitchens Ivon

- Hockney David

- Hutchinson Norman Douglas

- Jenney Neil

- Katz Alex

- Kentridge William

- Knifer Julije

- Kusama Yayoi

- Le Parc Julio

- Leciejewski Edgar

- Léger Fernand

- Levine Chris

- Marchéllo

- Martin Kenneth

- Mavignier Almir da Silva

- Miller Harland

- Mitchell Joan

- Modé João

- Moore Henry

- Morellet François

- Nadelman Elie

- Nara Yoshitomo

- Nesbitt Lowell Blair

- Nicholson Ben

- O'Donoghue Hughie

- Pasmore Victor

- Perry Grayson

- Picasso Pablo

- Pickstone Sarah

- Prehistoric Objects

- Riley Bridget

- Ruscha Ed

- Sedgley Peter

- Serra Richard

- Shrigley David

- Smith Anj

- Smith Richard

- Soto Jesús Rafael

- Soulages Pierre

- Spencer Stanley

- Taller Popular de Serigrafía

- The Connor Brothers

- Vasarely Victor

- Vaughan Keith

- Whiteread Rachel

- Wood Jonas

![Untitled [Water] - David Hockney](https://images.archeus.com/production/AC25-02-HOCKNEY-Water-Study-frame-crop.jpg?w=600&h=600&q=60&auto=format&fit=clip&dm=1759324888&s=3221efcb271df836a8c1f8fcc855c56c)